|

||||||||

|

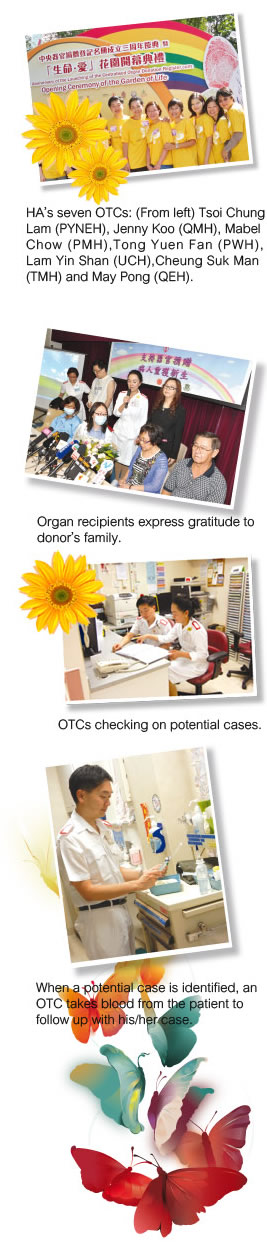

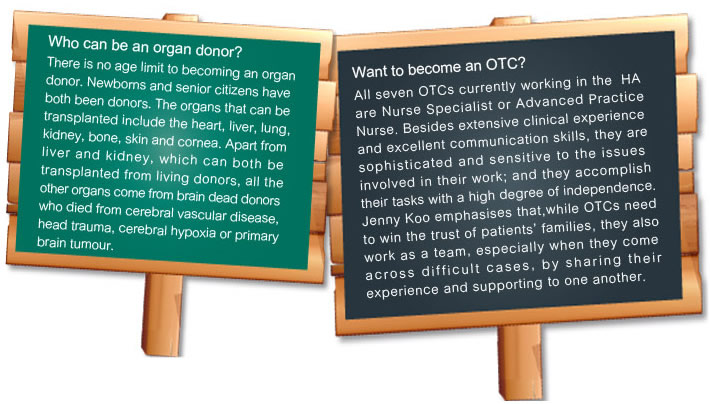

Hong Kong's first OTC started working at Queen Mary Hospital (QMH) in 1988. After years of development, there is now one OTC in each of the HA's seven hospital clusters. These professionals encourage organ donation and facilitate the matching of donated organs with potential recipients by working closely with the general medical, neurosurgical and intensive care units in each hospital. In addition, they keep a vigilant eye on referrals by frontline staff. They start close monitoring and doing follow-up procedures as soon as a potential case is identified. Although public awareness of organ donation has greatly increased in recent years, the number of people who need a transplant continues to rise faster than the number of donors. Around 2,500 patients are currently waiting in the queue. By helping to obtain prompt donations of organs from deceased persons, OTCs play a pivotal role in giving hope to others who are desperate for this chance to extend their life.

While it is hard for the relatives of a deceased to accept his or her sudden death, an OTC's primary job is to race against time in order to persuade them to make the donation. OTCs constantly face this situation. As Cheung Suk-man, OTC at Tuen Mun Hospital, puts it, it takes more than eloquence to convince a potential donor's family when so many other factors need to be considered. She says: "The most important thing is to help the family of the deceased to accept the reality that their loved one has passed away. We also have to explain every step of the organ donation procedure, especially the fact that the operation of removing the organ will not change the appearance of their loved one's body." To provide family members with fond memories of their departed one, Jenny Koo, OTC of QMH, recently volunteered to take on the role of a make-up artist. At the request of a deceased patient's family, she put the donor's favourite cologne, which he had used every day, on his body. His children felt reassured when they smelt the familiar scent; it was just as if they were with their beloved father once again. On another occasion, Jenny applied lipstick on a mother's dead daughter to make her look as good as she had in life. Jenny is happy to do this extra work, because it helps to comfort the families of the deceased. But the work of OTCs is more than getting consent for an organ donation. They also support families in coming to terms with the trauma of bereavement. "Sometimes, family members feel guilty about the death of their beloved. Then, it becomes the OTC's task to unravel this mental Gordian knot," Jenny explains. "It is an important moment. If it cannot be done immediately, the bereaved may go on blaming themselves for the rest of their lives." Nor does an OTCs' work stop after an organ has been donated. Tong

Yuen Fan, the OTC at Prince of Wales Hospital, notes: "The follow-up

work is the start of another mission." She remembers how a mother

was criticised by her neighbour for being "cruel" when she donated

the organs of her deceased 12-year-old daughter. To support the

disheartened mother, Tong offered to attend the daughter's funeral,

where she took the opportunity to tell her relatives and other mourners

how grateful the organ recipient had been. This relieved and encouraged

the grieving mother. |

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||